The Millerman School is an online school of political philosophy that offers courses on texts authored by Plato, Aristotle, Leo Strauss, Martin Heidegger, and other great thinkers. This article is my review of the Millerman School, having completed most of the school's courses and dozens of one-on-one tutoring sessions with Michael Millerman, founder of the school. Overall, the course content is extremely high quality, the school covers many texts that are not widely read today, and Millerman is an excellent and passionate teacher who clearly sees the deep social and political problems currently facing Western civilization. Millerman motivates the study of political philosophy as an essential means to clarify these problems and to ground political thinking aimed at their solutions.

This article is organized as follows. After providing a high-level overview of the school’s ideological architecture, I discuss Millerman's individual courses, reviewing the quality of their content and Millerman's teaching style. I then return to discuss the school architecture in more detail, characterizing the types of books that Millerman has chosen to teach and why, in my opinion, he has chosen them. I conclude with a discussion of the contemporary importance of the Millerman School in light of the deep cultural and ideological prejudices that have come to dominate academia and society at large. In a future article, I will provide a more detailed overview of each of the school’s courses to help interested students decide what to study.

School Architecture

Each of Millerman's courses covers a single topic or book relevant to political philosophy. Each course, in my view, serves one of three purposes which collectively define the architecture of the school:

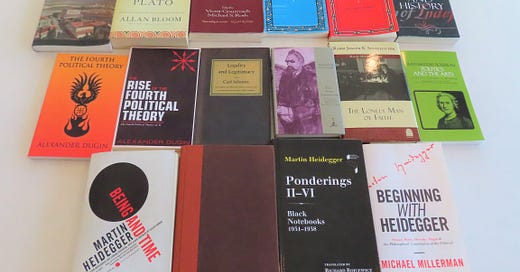

First, the school introduces us to a wide range of political thought, covering texts that are ancient and foundational, like Plato's Republic, and others that are contemporary and controversial, like Alexander Dugin's Fourth Political Theory. Much of this thought is poorly represented or outright suppressed today, largely due to ideological prejudices both inside and outside of academia. Millerman thus introduces us to books, authors, and ideas that we would otherwise not have access to, some of which required significant courage and sacrifice on his part to bring to us, a point that I will return to later.

Moreover, the school brings the intimate relationship between politics and philosophy to the fore, covering seemingly abstract philosophic texts, like Martin Heidegger's Being and Time and texts that more directly bridge the gap between politics and philosophy, like Leo Strauss's What is Political Philosophy? The school asks us to consider two questions about the relationship between politics and philosophy. First, can surface level political disputes be traced back to deeper disputes over a few, often unarticulated, abstract philosophic beliefs? Second, can we subject our a priori political opinions to rigorous philosophic questioning? For example, everyone has a vague understanding of courage and its political importance, but what exactly is courage?

Finally, the school's pursuit of seemingly esoteric political and philosophic questions is not driven merely by theoretical interest. Instead, it is driven by a desire to understand the current political crisis in the West as well as potential paths forward. Millerman's Philosophic Analysis of Masculinity course, for example, asks how the notions of man and masculinity have transformed throughout the history of political philosophy and shows how these transformations configure political debate about these topics today.

I will first discuss the quality of Millerman's individual courses before returning to discuss each of these points in more detail.

Individual Courses

Each course consists of a set of prerecorded video lectures that usually total between five and ten hours in length. Most are delivered exclusively by Millerman while a few are delivered to a group of students, interspersed with question and answer exchanges. The course content is impressive in breadth and depth, providing an accessible high-level guide to an often difficult text while at the same time showcasing the text's depth and richness. In so doing, Millerman trains us to read the text, the careful work of a great thinker, with the care necessary to properly understand the author's often subtle and nuanced teaching. Moreover, Millerman delivers the content with a passion that is both engaging and reflective of the critical importance of what he is teaching. It tells us that we are not seeking a merely academic understanding of the text, as if reading were simply a hobby to occupy our time, but instead that we are seeking essential knowledge about who we are, how we should live our lives individually and politically, and how we should begin questioning and thinking about these things.

The courses cover texts at varying levels of detail. Millerman's course on Heidegger's Being and Time, for example, focuses our attention on the movement of the book's high-level argument which easily gets lost in its notoriously difficult language and meticulous detail. As such, Millerman's course was an indispensable guide to my first reading of the book. Millerman's course on Nietzsche's novel Thus Spoke Zarathustra, on the other hand, covers nearly every page of the book in detail. While the high-level movement of Zarathustra is easy to follow, the book contains a wealth of nuance and, though not an overtly political book, raises many questions relevant to political philosophy that are easily overlooked. Though I had read Zarathustra before, Millerman's course greatly enriched my understanding of the book, especially its implications for political philosophy, and will serve as a further guide as I delve even more deeply into the book.

In addition to helping us understand the primary text, each course helps us understand political philosophy as a whole. Millerman is quick to recognize, and eager to point out, the primary text's often implicit connections to other texts. Through these intertextual connections, each course serves as a launching pad to discover many other high quality political philosophy texts. As such, Millerman’s courses served as indispensable starting points for my exploration of the vast canon of Western political philosophy.

Millerman highlights these connections in several ways, including short digressions during a lecture, rich question and answer exchanges with students, and bonus videos focusing on an explicit connection. These are seen, for example, in his Plato's Republic course. While discussing Socrates' rationale for banishing a wandering poet from his ideal city - that although the poet's poems are pleasing, they attack the gods and hence undermine political stability - Millerman points us to Rousseau's eighteenth-century Politics and the Arts (also covered in the school), which presents a similar rationale for opposing the construction of a theatre in Geneva - that the theatre would showcase entertaining but bad behavior which would encourage bad behavior among the citizens. Question and answer exchanges with students traversed many of the book's topics, including the soul-forming power of music and its potentially negative political implications. Here, Millerman directs us to the 1987 Closing of the American Mind by Allan Bloom, preeminent Plato scholar and translator of the Republic, for a discussion of the effects of contemporary music on education and politics which raises similar concerns. Finally, Millerman complements his discussion of the Republic's famous cave allegory with a short bonus course on Heidegger's treatment of the allegory which focuses on the idea of paideia and the "turning around" of the soul that education is supposed to accomplish.

These intertextual connections, while serving to direct a student's study of political philosophy, also reveal something very practical and significant about politics: that although the times and situations change, the fundamental problems of human and political life exhibit a noticeable permanence, echoing across the centuries and into our own age. We encounter ancient authors and characters in memorable scenes discussing issues of central importance to us today, issues like censorship, education, tyranny, justice and injustice, courage and cowardice, love, the best way to live life, and the best political regime. Moreover, far from treating these issues naively, as a first attempt which our civilization has long since surpassed, these books do the exact opposite: they provide fresh insights rooted in a sophisticated understanding of human and political life from which we have a lot to learn.

Collection of Courses

While each course is impressive in its breadth, depth, and contemporary relevance, so too is the collection of courses that Millerman that has selected for the school. Collectively, the courses introduce us to a breadth of political thought that is poorly represented or outright suppressed today. This breadth of political thought is complemented with philosophic depth that helps us analyze this thought and understand the intimate relationship between politics and philosophy. Finally, one course explicitly addresses a contemporary problem, showing how political philosophy can help us better understand the problem and potential solutions.

Breadth of Political Thought

Millerman's courses introduce us to a wide range of political thought which, in my view, can be categorized into three distinct realms. Each realm of thought presents us with an entirely different political worldview, one that implicitly or explicitly rejects certain key assumptions underlying liberal democracy, the governing structure of our regime. This rejection furnishes us with important critiques of our society’s dominant political worldview, but also subjects the realm of thought to distinct prejudices that inhibit its study today. I summarize these three realms of thought as follows:

Ancient Greek political thought, predominantly the thought of Plato and Aristotle, takes a comprehensive view of politics that focusses on the cultivation of human excellence and finding the best political regime. The Greeks' comprehensive view of politics differs wildly from our own which concerns itself with policies rather than molding excellent citizens and men. Moreover, many of the Greeks' conclusions are anathema today: that democracy is a fundamentally flawed political regime, that there is a fundamental division between the wise and the many, who cannot be made wise, and that technological progress is not a universal good, but is likely a danger when liberated from moral and political control, for example. This realm of thought is subject to two kinds of contemporary prejudice: the progressive prejudice which holds that it is out of date, irrelevant, and backward thinking, and the conservative prejudice that sees it as a mere historic relic, the foundation of Western civilization that young people "should" study, rather than something from which we can really learn.

Religious and mystical thought both recognize the legitimacy of transcendent personal experiences and the significance of man's spiritual nature. A transcendent experience provides access to knowledge that cannot be attained by reason alone and is politically relevant in one of two ways. It may be the direct revelation of a code of law, as the revelation from God to a prophet in the Biblical tradition, for example. Alternatively, it may broadly transform a man's understanding of his life and purpose, which has far-reaching, though subtle, political implications. Religious and mystical thought are primarily subject to two prejudices today. First, that they are anti-scientific, largely due to their belief in a supernatural realm that cannot be directly observed. Second, that they are anti-intellectual, largely due to the poetic or metaphoric language in which they are often expressed which is accused of intentionally obscuring their beliefs such that they cannot be rationally refuted.

Right-wing anti-liberal thought encompasses thinkers who can be broadly placed on the political right but who oppose certain fundamental assumptions underlying Western liberal democracy. Some such thinkers reject egalitarianism, for example, under the belief that it levels man and prevents human greatness from flourishing. Moreover, many of these thinkers call our common understanding of political topology as a left to right spectrum into question. Some reject the label of the "right" altogether, while others ask us to consider what the principles of a "true right," one not constrained by the bounds of liberal democracy, would entail. These thinkers face the most severe prejudices today, especially those directly or indirectly associated with twentieth-century National Socialist or Fascist political movements. Millerman's goal in presenting these thinkers is not motivated by an advocacy of these political beliefs, but instead by a desire to properly understand these thinkers so that we can accurately evaluate their ideas and determine what value they have to offer.

Philosophic Depth

In introducing us to these realms of political thought, Millerman provides us with many new ideas and worldviews to consider, each of which we may accept, reject, or modify to incorporate into our own political thought. While this greatly expands our political options, it is not Millerman's ultimate goal. Instead, he asks us to reflect more deeply on the nature of political thought and of politics itself by examining its philosophic roots. For this deeper philosophic analysis, the twentieth-century philosophers Martin Heidegger and Leo Strauss are central to the Millerman School.

Heidegger's thinking centers around the question of the meaning of being - we constantly use the phrases "to be" or "is," when we say "the door is open," for example, but what does this really mean? Although this question may seem useless or pedantic, it is actually the "question of all questions" that implicitly grounds all inquiry and knowledge, including formal scientific inquiry and our understanding of what it means to be a human being. Moreover, for Heidegger, the entire history of Western philosophy is fundamentally configured by a specific, distorted, understanding of being. This distorted understanding of being began with Plato and has finally run its course, culminating in the thought of Nietzsche. Heidegger, responding to what he saw as Nietzsche's completion of Western philosophy, sought to inaugurate a new beginning of Western philosophy, one that is fundamentally configured by a different, more authentic, understanding of being.

The question of how abstract philosophic thought, like Heidegger's, configures practical political thought is central to the Millerman School. Can all political thought be traced back to perhaps unarticulated or unknown underlying philosophic positions? Or does political thought operate independently and merely seek out philosophic justification after the fact, if at all? Millerman's PhD thesis and subsequent book Beginning with Heidegger: Strauss, Rorty, Derrida, Dugin & the Philosophical Constitution of the Political studies this general question within the intellectual landscape of the twentieth century, defined by Heidegger's philosophic thought and the responses to it by four preeminent political thinkers from across the geopolitical spectrum. Millerman's book explores two key questions. Can the wide disparity in these schools of political thought be traced back to a dispute over Heidegger's philosophy? Can Heideggerian philosophy serve as a basis for a fundamentally different politics of the future?

The intimate relationship between politics and philosophy, as well as the deeply practical import of this relationship, was perhaps best understood in modern times by Leo Strauss, who popularized the notion of political philosophy. "Political philosophy is the attempt truly to know both the nature of political things and the right, or the good, political order," writes Strauss in his 1954 book What is Political Philosophy? Everyone, Strauss argues, begins with an opinion of the good that implicitly guides all of his political actions. Simply put, he aims to change something, like a law, if, in his opinion, it is causing harm, or to preserve it if, in his opinion, it is causing good. Political philosophy emerges when he begins to explicitly question his opinion of the good in an attempt to acquire knowledge of the good.

This was precisely the goal of classical political philosophy, best exemplified by Socrates. Today, however, political philosophy has essentially vanished, according to Strauss. Many people today do not believe that there is such a thing as the political good, but instead that what is called good or right is a mere historic convention that varies with time, place, and culture. This belief makes the quest for knowledge of the good, the central goal of political philosophy, impossible. Strauss saw this as a terrible crisis for the West and vigorously fought to inaugurate a return to the classical ideal.

In so doing, Strauss developed unique insights into the true teaching of classical political philosophy as well as the contemporary crisis, both of which justify his centrality within the Millerman School. Through his meticulous studies and authoritative commentaries on classic texts, like Plato's Socratic dialogues, Strauss showed that these texts, and hence the true teaching of classical political philosophy, had been largely misunderstood for centuries. Consequently, for Millerman, the commentaries of Strauss and his students, like Allan Bloom, serve as preeminent exemplars for how to read, interpret, and teach political philosophy texts. Moreover, for Strauss, the contemporary crisis is not the result of a gradual waning of the classical ideal, but instead of a deep and deliberate ideological break with it. This break, initiated by Machiavelli in the fifteenth century, culminated in twentieth-century historicism. Historicism undermines the philosophic validity of the notion of the good and is consequently the primary antagonist of political philosophy. For Millerman, Strauss is essential for clarifying the contemporary crisis and showing what must be done to develop a deep political and philosophic response to it.

Contemporary Relevance

The central goal of most of Millerman's courses is to provide a high quality guide to a difficult political philosophy text. Implicitly, this sheds light on important contemporary problems. But it is also possible to proceed in the reverse direction: to start with a specific contemporary problem and ask how political philosophy can be used to direct our thinking about the problem. Currently, one of Millerman's courses, his Philosophical Analysis of Masculinity course, does this. The course begins with the contemporary problem of the assault on masculinity and asks how the view of man and masculinity has changed throughout the history of political philosophy, from Plato to Heidegger. Through this exposition, the course helps us understand how the contemporary problem arose, illuminates the philosophic depth of the problem, and gives us options for thinking about man and masculinity today.

Millerman originally developed this course for a group of politically, though not academically, minded men concerned about the constant assaults on masculinity today. I see this as evidence of an important cultural phenomenon that is emerging, largely in response to the ideological fanaticism of the political left that has come to dominate academia and society at large. On the one hand, there is a growing recognition of the depth and danger of this fanaticism and hence a growing demand for a deep political and philosophic response to it. On the other hand, there is a growing supply of highly intelligent, courageous, and passionate teachers, like Millerman, who have been effectively pushed out of academia and other mainstream professional institutions early in their careers and have consequently been forced onto an entrepreneurial path, operating outside of these institutions. It was this dynamic that facilitated my connection with Millerman.

I first learned about Millerman in the late 2010's while I was pursuing a PhD in computer science. During this time, I witnessed the left's ideological fanaticism first hand. It was genuinely shocking to see graduate students - who are now professors, lawyers, and engineers at prominent tech companies - celebrating violent riots, attacks on police officers, the shouting down of speakers, and open racial hatred against whites, or to see university leadership demanding cult-like adherence to the vacuous ideology of diversity, openly supporting and reciting the slogans of violent, ideologically aligned protest groups in the summer of 2020, and abusing their official platforms to condemn a presidential candidate they disapproved of. Even more shocking was the fear of dissent that dominated the entire campus, down to everyday conversations, and the fact that this was not seen as a problem, that persistent attempts by myself and a handful of others to raise awareness of and to fix the problem were largely ignored or met with contempt.

During this time I learned that the ideological fanaticism that dominated campus life also dominated the politically oriented academic disciplines, though in a different form. For me, Millerman's plight was a primary example of this. Millerman was pursuing a PhD in political science, studying the impact of Heidegger's philosophy on thinkers from across the geopolitical spectrum, as I discussed above. Several professors on his PhD dissertation committee attempted to sabotage his completion of the program by resigning from the committee and attempting to terminate his funding. They primarily objected to his interest in the contemporary Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin, a stern critic of Western liberal democracy from the right, and his decision to include Dugin in his dissertation study. The professors claimed that Dugin was not worthy of legitimate academic study due to his political views and the contemporary political actors associated with him, both of which they characterized as "fascist." Millerman bravely refused to cave to the pressure to denounce Dugin and was eventually able to assemble a new dissertation committee and graduate in 2018. He was, however, severely ostracized and it was clear that he was not welcome to pursue a career in academia. This was his impetus to start the Millerman School, bringing high quality political philosophy education to students outside of mainstream academia.

I started studying with Millerman in the fall of 2021, after completing my degree in late 2020, at a time of national cultural and political turmoil. Upon entering graduate school, I would have thought that the universities would bring clarity, sober debate, and intellectual guidance, protection, and fortitude to a nation in crisis. Upon exiting, however, I understood that they were doing the exact opposite. I left with a clear understanding that a deep cultural, spiritual, and intellectual war was being waged on America and the West, and with a strong sense of duty to fight back. I left without a concrete plan, only with some ideas that have guided my life since then: cut ties with mainstream professional and intellectual institutions and earn money freelancing remotely; travel America, living in different cities in the interior of the country, to better understand the nation, its people, roads, landmarks, small cities, and unknown treasures, in order to more deeply understand what it is that I am trying to save; train jiu-jitsu and other martial arts to defend against increasingly regular political violence; read Great Books, to understand the history of the West, to sharpen my intellect against the greatest thinkers of all time, and to train myself to write, a critical weapon that I will need for my mission.

I saw Millerman as someone who could help me with my mission. From the quality of his publicly available lectures and the courage he demonstrated during graduate school, I recognized him as a highly intelligent and knowledgeable teacher, someone who sees tremendous treasure in the books that he teaches, something much higher, something worth sacrificing his career to pursue authentically and to share widely. Moreover, I saw that he understands the magnitude of the contemporary crisis and consequently that his pursuit is motivated in part by a sincere desire to fix it.

After studying with Millerman over the past two years, my initial impression has been confirmed. I have learned a tremendous amount from his lectures and our one-on-one tutoring sessions. He has vastly expanded my understanding of Western political philosophy and has been a great help in my large undertaking of the study of Great Books. Moreover, he has helped me become a better and more precise thinker, reader, and writer, all of which I will utilize in the writing and entrepreneurial projects that I am now beginning. For all of these reasons, and the reasons that I stated throughout this article, I highly recommend the Millerman School of political philosophy.

Anyone want to start a Millerman School reading club?